| Frost Town Main Page | Frost Town Archeological Invesigations | HAS Frost Town Screening Project |

History of the Frost Town Site, Houston, Texas

Early History

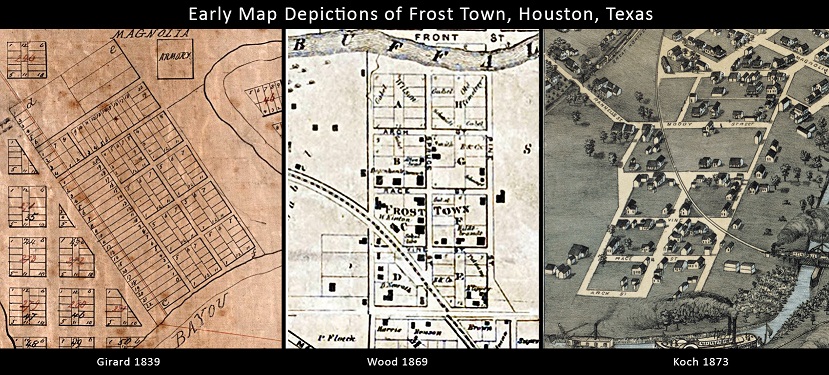

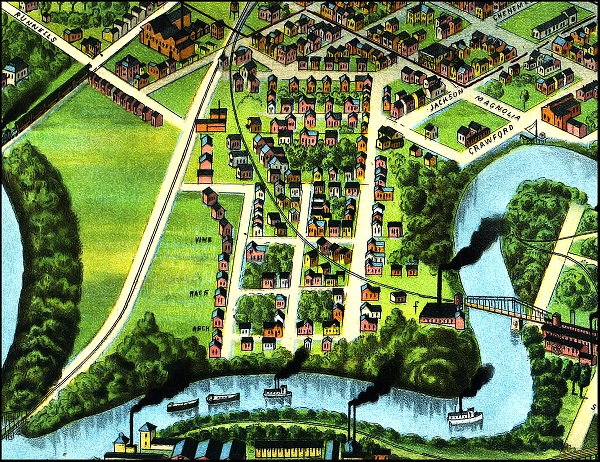

One of the earliest settlements in the Houston area was located within a prominent horseshoe bend along the southern banks of Buffalo Bayou, less than one half mile east of Allen’s Landing. This area was part of an 1824 Mexican land grant to John Austin, although the earliest settlement on or near this location may have occurred as early as 1822. Jonathan Benson Frost built a home and settled there sometime after July 1836, and Austin sold this portion of his land holdings to the Allen brothers in August 1836. Frost then bought the land where he had located his home, including about 15 acres in the horseshoe bend, from the Allen brothers in April 1837. A platted subdivision is illustrated within the bayou bend at this location on an 1839 map of Houston (Girard 1839), which by this time had become known as the community of Frost Town (see Note 1). Early maps show that Frost Town was originally comprised of eight city blocks that were designated as Blocks A–F (Girard 1839; Wood 1866, 1869). By the 1880s, Frost Town had expanded to include additional blocks east, west, and south of the original eight-block area. The residential area to the south, called the Moody Addition, was commonly referred to as part of Frost Town in Houston City Directories printed between 1880 and 1905. Two bird’s eye views of Houston show that the Frost Town area was a well-developed neighborhood by 1873 (Koch 1873) and densely settled by 1891 (Westyard 1891).

Note 1: The Houston newspaper, Telegraph and Texas Register, contains many mentions of the “Frost Town” community from 1839 to the 1860s, as revealed by searching online newspapers on the Portal to Texas History. The following issues of the Telegraph and Texas Register contained mentions of “Frost Town” or “Frost town”: October 2, 1839 (Vol. 5, No. 11); April 8, 1840 (Vol. 5, No. 29); February 17, 1841 (Vol. 6, No. 13); February 22, 1843 (Vol. 8, No. 10); March 1, 1843 (Vol. 8, No. 11); April 26, 1843 (Vol. 8, No. 19); March 18, 1853 (Vol. 18, No. 11). The Weekly Telegraph has mentions of “Frost-Town” on October 9, 1860 (Vol. 26, No. 32) and October 6, 1860 (Vol. 26, No. 33). The 1895 map called City of Houston and Environs labels the eight contiguous blocks as “Frost Town” (Whitty and Stott 1985).

|

|

Early Map Depictions |

Westyard 1891 BirdsEye View |

Development and Decline

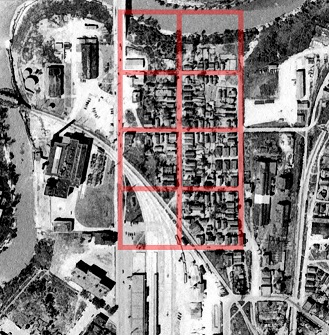

1944 Historic Aerial

Much of the areas just north of the bayou and immediately south of Frost Town became industrialized during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with businesses centered on the areas expanding railroad yards. The Galveston and Red River Railroad built two miles of track south of Frost Town in 1855, changing its name the following year to the Houston and Texas Central Railroad (H&TC). In 1865, the Galveston and Houston Junction Railroad (G&HJ) was completed, connecting the H&TC south of Buffalo Bayou with the GH&H north of the bayou. The G&HJ Railroad line ran across the southern portion of Frost Town, and it included the first railroad bridge across Buffalo Bayou. It was during this period that witnessed the rapid industrialization of Houston’s Second Ward that Frost Town began to experience economic decline.

By 1890, the German-period wood frame and log houses were 30- to 50-years old, and the community was described as a “dreary huddle of shabby houses” (Aulbach 2012:443). Public service systems, such as gas, electricity, telephone, and water, came to Houston between about 1870 and 1900. A private water system was built in 1879, and it eventually was taken over and expanded by the City of Houston in 1904 (Roberts 1929:n.p.). Houston’s downtown area and the city’s affluent neighborhoods were among the first to receive public utilities, with other areas of the rapidly expanding city receiving them -often piecemeal- over the next few decades. Public services make their way to Frost Town only slowly, with some areas of the community still not on the city sewer system as late as the early 1950s. By the middle of the twentieth century, the community (which had become colloquially known as El Barrio del Alacran in the 1930s) had become “one of Houston’s worst slums” (Aulbach 2012:451, citing article by Byrd 1952). When compared with the affluent neighborhoods downtown and business district, the poverty-ridden and neglected Frost Town community offers a striking socioeconomic contrast.

Construction of Eastex Freeway (US 59), ca 1957 - 1958

Frost Town’s economic decline unfolded slowly over several decades as increasing industrialization and urban development chipped away at the character and cohesiveness of the Second Ward. The pace of decline notably increased in 1926 when a large portion of southern Frost Town was removed to make way for the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad (MK&T) terminal. During the 1950s, the eventual demise of the Frost Town community became inescapable when large portion of the original neighborhood was destroyed during the construction of the Elysian Street Viaduct and the Eastex Freeway (now U.S. Highway 59). As of 1955, only a few of the old wood frame houses of old Frost Town existed. The former Frost Town/El Barrio del Alacran neighborhood essentially disappeared by the 1970s, and by 1990, only six wood frame homes remained standing. The last remaining home was removed by 1999 (Aulbach 2012:453).

Demographic through Time

1957 photo of the 600 block of El Barrio Alacran,Houston, Texas.

German laborers were among the earliest residents of the Frost Town community, and they would continue to dominate demographic of the neighborhood for many decades. Germans immigrants settled in virtually every area of Houston, but the Second Ward became an unofficial hub of German-American culture and social life during the nineteenth century (McWhorter 2010:40). The typical household in the community’s German period (ca. 1840 through the 1870s) was “a blend of a rural homestead in an urban environment.” Describing the houses and other improvements, Aulbach (2012:428) states:

“The homes in Frost Town were modest and similar to many of houses of the period. A typical Frost Town residence was a white frame cottage built of cypress as a square dog-trot with three rooms on each side of a central hall and a roof sloping over the front porch. The roof had central dormer windows front and back to provide light to the loft, and there were separate buildings for the kitchen, a well house, a smokehouse, a wash house, a chicken house, a barn, and a privy.”

During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, early European immigrant families increasingly moved to other parts of Houston (and to other areas of the state), and Frost Town rapidly transitioned into a predominantly African American neighborhood. At the turn of the century, the Frost Town neighborhood had 143 households (families and single adults), of which 55.9 percent were black, 44.1 percent were white, and none were Hispanic (Aulbach 2012:443–444). In 1920, Frost Town population was 49.4 percent black, 20.1 percent white, and the Mexican population had increased significantly to 30.5 percent (Aulbach 2012:444). In the 1920s, the ethnicity was shifting again, and the 1930 census listed the population as 65.8 percent Hispanic, 24.2 percent black, and 10 percent white (Aulbach 2012:445). During this later Hispanic-dominated period, the old Frost Town neighborhood became known as El Barrio del Alacran—the Scorpion neighborhood.

References Cited

Aulbach, Louis F.

| 2012 | Frost Town. In Buffalo Bayou: An Echo of Houston’s Wilderness Beginnings, pp. 385–482, by Louis F. Aulbach. Louis F. Aulbach, Publisher, Houston, Texas. |

Byrd, Sigman

| 1952 | Frosttown: The Vision & the Nightmare.” Houston Press, February 26, 1952. Subdivisions—Frost Town, Vertical Files. Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston Public Library, Houston. |

Girard, A.

| 1839 | City of Houston and its vicinity, drawn and partly surveyed. Hand drawn map and survey of City of Houston and its Vicinity drawn and partly surveyed by A. Girard, Late Chief Engineer of the Texas Army, January 1839. Scale 400 feet to one inch. Digital Scholarship Archive online, Rice University. Electronic document, http://scholarship.rice.edu/handle/1911/64072?show=full , accessed January 15, 2014. |

Koch, Augustus

| 1873 | Bird’s Eye View Of the City of Houston, Texas, 1873. Lithograph (hand-colored), 23.2 x 30.1 in. Published by J. J. Stoner, Madison, Wisconsin. Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin. Amon Carter Museum online.

http://www.birdseyeviews.org/zoom.php?city=Houston&year=1873&extra_info=, accessed April 21, 2009. |

McWhorter, Thomas

| 2010 | From Das Zweiter to El Segundo, A Brief History of Houston’s Second Ward. In Confronting Jim Crow. Center for Public History, University of Houston. Houston History 8(1):38–42. |

Roberts, Ingham

| 1929 | ”Fifty Years Ago Houston had 42 Saloons, 21 Dry Goods Stores, 98 Groceries for 16,513 People.” In The Houston Chronicle, Pioneer Section, May 26, 1929. |

Westyard, A. L.

| 1891 | Houston, Texas (Looking South). Lithograph (hand-colored), 23 x 42.6 in. Copyright copy inscribed by D. W. Ensign, Jr., Chicago. Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth. Amon Carter Museum online. Electronic document, http://www.birdseyeviews.org/zoom.php?city=Houston&year=1891&extra_info=, accessed April 21, 2009. |

Wood, W. E.

| 1866 | Map of Houston, Harris Co., Texas [prepared for the city directory]. Pessen & Simon Lithographers, Houston.

Available at Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston Public Library, Houston. |

| 1869 | Map of Houston, Harris Co. Available at Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston Public Library, Houston. |

To learn more about this project contact the HAS President: president@txhas.org

| Frost Town Main Page | Frost Town Archeological Invesigations | HAS Frost Town Screening Project |